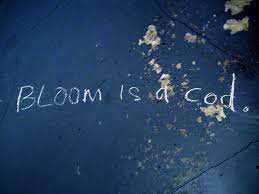

The violent events in Dublin’s city centre on Friday 12 May 2023 when groups of Dublin based people set upon five hundred plus asylum seekers, forced to live in tents outside the International Protection Office in Sandwith Street, setting their belongings on fire and shouting racist abuse at them were very troubling indeed. Lawyer and activist Gary Daly, who came to stand in solidarity with the asylum seekers, wrote on his Facebook page that what was particularly disturbing was that “the people threatening extreme violence or calling all refugees ‘rapists’ sounded just like me. They were Dublin voices… I recognised the accents, but I was a stranger to the language used. Claiming that we (those standing between them and the homeless migrant camp on Sandwith Street) were all ‘anteefa’ or ‘government shills’ or ‘paid NGOs’. This language is imported only very recently from far-right America.”

Following the Ukraine refugee crisis, the number of people seeking international protection in Europe has grown exponentially. Ireland is currently housing 19,874 asylum seekers, including 4,139 children, in 172 locations around the country. This is a 90 per cent increase in a year and a 266 per cent increase since 2018. Although still high when compared with pre-2022 figures, the number of applications has gone down considerably in recent weeks according to data provided by the Department of Justice.

The much-criticised Direct Provision system, inadequate as it was, and epitomising Ireland’s ‘asylum industrial complex’ whereby private landlords and hotel owners had been paid millions of euros to house thousands of asylum seekers by the government, that is, by Irish tax-payers, as Vukašin Nedeljković and I reported in Disavowing Asylum: Documenting Ireland’s Asylum Industrial Complex, is no longer able to cope. Hotel owners have reverted to the more profitable tourism business which the government prefers to nurture at the expense of accommodating applicants for international protection, and hotels are no longer available. Due to Ireland’s disastrous housing and homelessness crisis, the result is a huge shortage of accommodation to newly arriving asylum seekers, 580 of whom are currently camping on the streets of Dublin, some in tents outside the ironically named International Protection Office, where they have been subjected to appalling racism by what has been described by some activists as ‘fearful local working class communities’ rather than by white Irish racists.

Continue reading “Sandwith Street: ‘Whiteness riots’ and ‘local’ white communities”

You must be logged in to post a comment.