Paper presented at the Global Ulysses seminar, 14 June 2022

One of the Hebrew language books I took from my parents’ Haifa home when I came to Ireland with my late partner Louis Lentin was מלחמת האירים לעצמאותם –The Irish War for their Independence written by a Jewish emigrant from Ireland, one Efraim Schwartzman, who gifted it to my parents. He was my grandparents’ neighbour in the Jerusalem neighbourhood of Talpiot, in my native mandatory Palestine.

The book, published in 1947, is dedicated to Schwartzman’s sister and her family who were killed in the Romanian ghettos of Transnistria, where many members of my own Bucovina Jewish family had been exiled to during World War II.

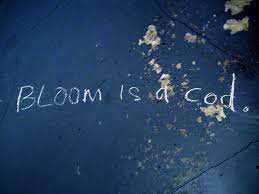

These two serendipitous points – Schwarzman’s northern Romania Jewish family, and his Irish origins – must have been the fateful omens that led me to Ireland, a country I was barely aware of prior to meeting Louis in Israel television. Arriving in Dublin in 1969 – jumping from the Israel-Palestine frying pan to the Northern ‘Troubles’ fire – was made easier by taking Bloom as my flanneur-stroller guide through the estrangement of late sixties Catholic Irish society. Under Louis’s guidance I spent my first year – in a rented apartment in the ironically named Zion Road – reading Ulysses complete with guidebooks and concordances…

Irish Jews make great copy. After all, as the late David Marcus asks, ‘Who has ever heard of an Irish Jew?’ Schwartzman’s book deals only briefly with the history of the Jews in Ireland and came out after Bernard Shillman’s A Short History of the Jews in Ireland (1945). Since then there were quite a number of books, articles, theses and television documentaries about the Irish Jewish community. Quite apart from David Marcus himself who returned obsessively to what he called his hyphenated Jewish identity, in Next Year in Jerusalem (1954), A Land not Theirs (1986), Outobiography: Leaves from the Diary of a Hyphenated Jew (2001), and Buried Memories (2004), there were Louis Hyman’s The Jews of Ireland(1972), Dermot Keogh’s Jews in Twentieth-Century Ireland: Refugees, Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust (1998), Cormac O’Grada’s Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce: A Socioeconomic History (2006), Ray Rivlin’s Shalom Ireland: A Social History of the Jews in Modern Ireland (2003), Memory of an Irish Jew by Lionel Cohen, Rory Miller’s The Book of the Irish: Irish Jews and the Zionist Project, 1900-1948 (2011), and the outlying Irish Sephardim- A Memoir from Ireland’s Hidden Jews, by Kelly Gill Seymour (2016) – definitely not an exhaustive list. And I cannot count the number of times I have been asked for interviews for magazine articles, television programmes and postgraduate dissertations. So yes, Irish Jews are great copy, clearly a tradition established by Joyce.

I suppose I should have consulted Schwartzman’s book in writing my chapter. For instance his claim that the names of the first three Jewish people arriving in Ireland in the year 1600 after the expulsion from Spain were Freira and Faro – Murano Jews who had escaped the Spanish Inquisition and who registered as Protestants when they arrived yet continued to stealthily keep their Jewish religious customs. Indeed, many of the early Jews in Ireland were Sephardi – only later was the community made up of Lithuanian pogrom refugees. He also recounts that in 1689 forty five rich Jews contributed 45,000 pounds towards funding the English invasion of Ireland; and that the Jewish community in Dublin was the second largest in Britain after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. He describes the Irish liberation movement’s sympathy for the Jewish people and cites the founder of the Zionist movement Theodor Herzl describing himself in a 1895 diary entry as the ‘Jewish people’s Parnell.’ But perhaps most sensationally, Schwarzman claims that Parnell’s mother Dalia Tudor came from a Jewish family, who had been exiled to Spain…

Continue reading “Ulysses, race and the new Bloomusalem”